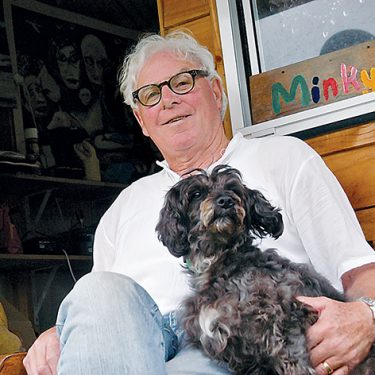

WHILE every author draws on life experiences to form a narrative, not every author has such a rich and at times dark background as Klaas Kalma.

His upbringing within a dysfunctional family in war torn Holland, journeying to Australia and learning how to speak English among strangers provides a rich lode to be mined and woven into the fabric of his first novel, Creeping Shadows.

Written at the urging of a close friend, the self-published book has sold more than 10,000 copies online and, according to a librarian, has no time to gather dust on the shelves at the lending library in Mornington.

Now 74, Kalma describes himself being “confident in my ability to overcome adversity and challenges”.

“You can’t succeed without an ego and I’ve always had the will to succeed, I’m like a dog with a bone.”

At home in Mt Martha, Kalma says his friend “Kerry” had always encouraged him to write about his life, but he thought “autobiography is too indulgent, so I fictionalise my life experience”.

So Creeping Shadows is fiction, mixed with thinly disguised real events. There was no need for Kalma to stray far from reality to find a compelling narrative.

Expecting to “work until the day I die”, he’s completed a second manuscript and hopes to have Distant Echoes published before year’s end. This time around publisher Fremantle Press has picked up his ideas.

Always an avid reader, Kalma had read most books by Jules Verne by the time he was 10. At school in Holland art and sport were the only two subjects he remembers being good at.

“I was growing up in a war zone. My parents were involved in the resistance and so I was a street kid from very early on.”

He recounts seeing the occupying German troops shoot a man in the street before being ushered inside by his mother.

“What you see is normal and I saw a lot of stuff.”

Kalma’s parents – “who I never felt wanted me” – split up following “a few normal years” after the end of the Second World War, which led to him being brought to Australia by his mother and her new husband.

His brother remained in Holland with his father and grandmother, although they eventually went to New Zealand. Kalma’s father remarried and, before dying in a car accident at 49, had another six children.

But for Kalma, Australia meant basically being dumped by his mother on a farm where he was given lodging and food in return for work. After two years he was offered and accepted a paying job on another farm.

He didn’t attend school in Australia and his mother and her second husband, his stepfather, returned to Holland after five years, “separately and without telling me”.

His mother also never explained, “what happened” between her and Kalma’s father.

Left to his own devices Kalma “worked at the abattoirs in Dandenong and lived on the streets in Coburg”.

There were bikies and street fights, more fodder for his late life emergence as a novelist when he learned to “separate yourself from your characters to be able to write objectively”.

After some years working at various jobs Kalma applied for a university studentship, quickly getting naturalised and lying about having obtained his matriculation in Holland (the papers were on their way) and went on to meet his future wife, an art student Prahran college.

“She made me want to change direction. I decided I’d better shape up – her family was the first family I’d really known.”

They married and had three children. Their daughter died of cancer at 12 and his wife, after they separated, also succumbed to cancer when she was 40.

“I wasn’t a good father and didn’t understand marriage and children,” Kalma says, adding that he’s close to his two sons and his five grandchildren and “got on fantastic” with his wife, even after separating.

He has been married to Sue, his fifth wife, for 22 years. He says Sue “came as a package”, with two children of her own.

“I went off the rails a bit after my [first] wife’s death, I just couldn’t settle. There were no bad relationships, but I’d get bored and couldn’t sustain enthusiasm,” Kalma says.

“I don’t know if all people change significantly as they age, but I’m light years away from the self-centred prat I was at 20.

“As we go through life we make terrible mistakes, but it’s what we make from them … hopefully I now have more empathy and consideration for people and things than as a young man.”

Kalma, who also paints and plays guitar (“although I know I’ll never be a musician”) believes everyone to be “gifted in some way” and feels privileged to “being part of the arts”.

“But it’s amazing how few people find [this] out because they never challenge themselves.

“It was pure survival when I came here. I was made to do abhorrent things, like killing animals.”

A psychology major, Kalma is interested in seeing “how people tick”.

“We all react differently to pressure; there is no end to trying to understand how people think.

“Why do people listen to music? I saw a documentary where dementia patients lying bed started moving and reacting to music.

“These are unanswered questions. Life is a journey along a path that is usually of your own choice.”