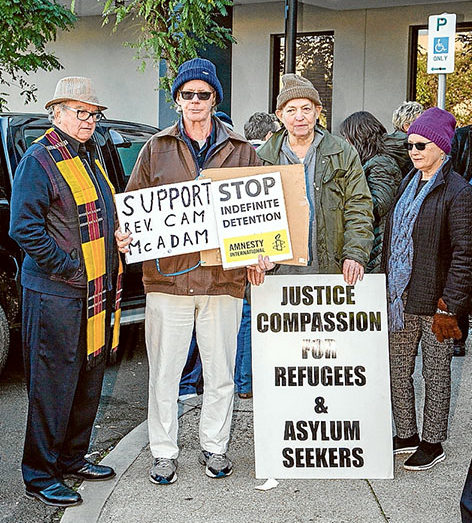

THE seven protesters who were arrested and charged with trespassing after refusing to leave the Hastings office of Flinders MP Greg Hunt all say they were frustrated by the refusal of governments to be more compassionate in their treatment of refugees and asylum seekers.

The sequel to their protest played out in Frankston Magistrates Court last week, more than a year later.

Despite prosecutors offering six of them the chance to avoid a court appearance, they elected to appear as charged and read out statements to explain their decision to deliberately flout the law.

Here are some edited extracts:

Cameron McAdam, minister, Uniting Church, Mt Eliza: On many occasions, my letters to MPs have received a reply that does not even address the issues raised and simply provides pat party lines.

In April last year I read about a five-year-old Iranian girl, temporarily in Darwin because of her father’s health, who suffering from PTSD, had attempted suicide under fear of being returned to Nauru. Much of my ministry life has been spent caring for children such as these. My own boy at the time was four. My faith calls me to care for the vulnerable and I could not look my own children in the eye in years to come and say I did nothing to help these vulnerable people supposedly in our nations care.

I knew the action we took, alongside similar actions taken by hundreds of other church leaders around the country, bi-partisan actions, would be peaceful and non-violent and that we would treat everyone we encountered with respect, and yet be clear of our message to Greg Hunt and the wider political community that locking up these children is wrong.

Timothy Johnson: I have been very privileged to experience the freedom, opportunity and safety that Australia provides. As such, I feel that I have a responsibility to live in such a way that enriches and betters the lives of the vulnerable, the marginalised and the persecuted. I consider it important to hold our nation’s leaders and elected officials to the same standard.

Kristen Furneaux, theology student: I grew up in Somerville and Mt Martha where I enjoyed an uplifting education at Flinders Christian Community College. My involvement with this Love Makes a Way action was indeed another contributing avenue for my understanding of faith and social responsibility. I chose to participate in this movement as a peaceful and considered response to the treatment of asylum seekers, which deeply saddens me as an Australian citizen and a fellow human being. As a dedicated community volunteer, I feel that it is my responsibility to use the privileged circumstance of my life on the Mornington Peninsula to create change in the lives of those who have not been fortunate enough to feel a sense of belonging or safety in their own community.

Jake Doleschal, theology/arts student, community development worker with Urban Seed: I began teaching Sunday school at a local church when I was 19, and it was then that I became unable to reconcile my professional duty of looking after and ensuring the safety of the 70 kids in my care on a Sunday morning, with my nation’s inability at ensuring the safety of kids in detention on a Monday. I work with vulnerable people … [and] am unable to go home at night in the knowledge that that evening there are young people in offshore detention who do not have a home that is safe, who are in danger of abuse and experiencing such hopelessness that they may self-harm, swallow poisons or set themselves on fire.

Dean Moroney, theology/arts student, Frankston City Council youth worker: On a trip to Bali as a 19-year-old I met a family who were fleeing persecution in Iran. They had a beautiful little boy who would have been about six. They told me of their persecution, of their struggles in Bali and their desire for a better life. But they were in limbo, a family without a home. My heart broke for them, and especially for their son. They had little hope – I’m not sure where they are today. While volunteering with Urban Neighbours of Hope I met a man at Broadmeadows detention centre. He was my age, only 19, and the expression of hopelessness and despair in his eyes is something that I will not forget.

Simon Reeves, Baptist minister: After inviting a young Sudanese refugee to move into our home many years ago and hearing his story from war-torn Sudan, I have never been the same. I have been committed to working for peace and learning how to welcome people who have been affected by violence and displaced by conflict. … Until this nation changes its ways, I expect no consequences will deter me from doing whatever I can to protect the most vulnerable people in the world at this moment – children and families seeking refuge from harm.

Joel Furneaux, youth worker: I can assure the court that while sitting in quiet prayer and reflection in Mr Hunt’s office, it was not a statistic that I prayed for, nor was it an irrelevant ideology. When I closed my eyes in prayer, it was the faces of young men who had told me [while working for Anglicare] of the homelands they had been forced to flee because of the sickening actions of Al Qaeda.