WITH daily media reports of the increasing number of people around the world diagnosed with COVID19, irrational hoarding and profiteering, I am cast back to my childhood and epidemics of a virus that closed schools, swimming pools and cinemas around the world.

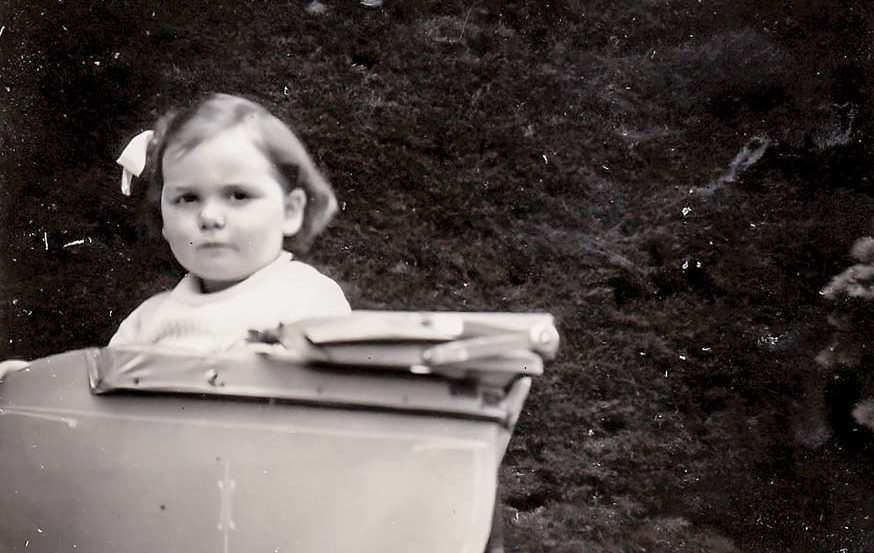

In 1946, my family was quarantined after I was diagnosed with infantile paralysis, or poliomyelitis. My parents never spoke about how they were treated in that small Gippsland market town (you don’t talk about the war) and I don’t remember, but many suffered greatly.

Neighbours crossed the road to avoid the infected; people became prisoners in their own homes, trying all manner of dopey repellents such as clothes pegs on the nose (no affordable gauze masks in those days).

In Iron Wills, Victorian Polio Survivors’ Stories, Dorothy Dunlevie told how on the day she went to Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital, the health department moved in and fumigated her family’s home.

Polio was seen as a “dirty disease” and deeply feared. Orthodox medicine could not cure it, only manage the pain and encourage recovery while preventing deformity.

The virus could spread hand to mouth and seemed to thrive in summer (although I got it in winter) attacking cells in the spinal cord and brain stem, causing paralysis of limbs and respiratory system.

Children were the most vulnerable, isolated, hospitalised, many not seeing parents for years. From the early 1930s at Mt Eliza, the orthopaedic branch of the Royal Children’s Hospital treated polio and tuberculosis.

There were many dopey, well-meaning ideas for treatment there too, like putting children naked, in splints, out in the sun for “heliotherapy” (hello melanomas). But Mt Eliza had a good hydrotherapy pool, swimming was good, building back muscles and lungs not too badly affected.

In 1956, Salk and Sabin perfected their vaccine and Victoria had it quickly thanks to CSL scientist Dr Percival Bazeley, of Orbost, working in the US with Jonas Salk.

But, before that, in 1954 came the royal visit to Australia of the new Queen Elizabeth. To prepare for the tour, terrified of the Queen being exposed, the government introduced a soap and water hand washing campaign, that polio experts today credit with helping stop the spread of epidemics.

An outbreak of polio in Western Australia (catching opposition leader-to-be Kim Beazley) had Prime Minister Robert Menzies insist the royal party sleep on the royal yacht and eat only food prepared on board.

Unlike the stream of information about every positive and negative COVID19 swab today, similar figures were not kept on polio diagnoses and deaths. Many deaths were concealed as respiratory failure or similar, making it impossible to impress authorities with numbers of people experiencing late effects of polio today, including siblings with mild or undiagnosed cases wondering now what is wrong with them.

So, what is happening today with another virus on the march? Why are some Australians so focused on toilet paper?

Americans are stocking up on canned food; Italians on pasta; Indonesians on herbs and natural remedies. And all wearing face masks that generally are effective only for the first half hour.

Reason and resourcefulness have departed. Those vulnerable to COVID 19 have already-compromised respiratory systems – the elderly and very young. If we do as advised, avoid shaking hands, wash hands properly with soap and water, eat a fresh balanced diet, exercise, enjoy the fresh air, care for each other, contact is highly unlikely. Right?

Mornington Peninsula Post Polio Support Group, informing and supporting polio survivors, their families, carers and health professionals, meets from 11am on the second Saturday of the month at Mornington Information Centre, corner Elizabeth and Main streets, Mornington. Details: 5979 7274 or polionetworkvic@gmail.com

First published in the Southern Peninsula News – 17 March 2020