LIKE most people who have experienced the evils of war and returned home, the horrors of starvation, family separation, and physical and emotional abuse often travel with them and continue to silently haunt their memories.

Film producer Thomas Watson knew the emotional and physical torture his Dutch-Indonesian grandmother Yvonne Watson (nee Holman) suffered at the hands of the Japanese Imperial Army during WWII was deep and painful, but he, nor anyone else in the family, dared speak of them.

Now, with the passing of his beloved grandmother in 2013 at the age of 91, and a few years of digital story-telling under his belt, Watson has decided the shocking history of the treatment of internees during the Japanese invasion of Indonesia – which had been a Dutch colony for 300 years – needed to be told.

He and filmmaker Jean-Baptiste Breliere have researched the experiences of internees in the Indonesian camps where his grandmother and hundreds of others were enslaved after the Japanese occupation and until being evacuated by the Australian Red Cross in 1946.

The result is the documentary, The Past Ended on Mango Street, a moving and confronting film about war crimes committed in the Asia-Pacific theatre of WWII.

“It’s such an obscure period of the war, and there really wasn’t much written about the way the Dutch were treated in the concentration camps in Indonesia,” Watson said.

“But it is well known that they were often mistreated, beaten and starved, and some of the women were used as comfort women, or sex slaves.”

While he did not uncover the whole story about the treatment of his grandmother, Watson said he came to realise that families all over the world continue to hold the pain of loved ones lost at war, or of those who returned with so much horror to tell they could say nothing.

“My grandmother never spoke of the war, she had a reserved nature, a kind of stoic quietness, but the family knew that she had suffered,” he said.

“I loved my grandmother, she was a much-respected part of the family, but I wish now that I had been able to get closer to her and I regret I didn’t talk to her more.

“I think she was traumatised and that led to her silence. As a family we were terrified that asking would make her relive those experiences and we didn’t want that.

“She did say some things at times, but they didn’t have much context without really knowing what went on. It wasn’t until I started my own investigations that I discovered how bad things were in the camps, and that my grandmother had been crammed into a small room with 15 others and forced to work in the Japanese garden, beaten and starved.

“One story I remember my aunt telling me is that the women had to wear aprons to weed in the hot tropical sun. One day my grandmother returned from work and her apron wasn’t dirty, so they beat her severely because they assumed she hadn’t been working hard enough.”

Family separation was a strategy of the Japanese Imperial Army in the camps, and while the-then 24-year-old ‘s two younger brothers and her mother were in the same camp, they were forbidden to contact or to talk to each other.

Her father escaped internment because he was considered “native Indonesian”, until one day he was caught listening to a foreign broadcast about the war and beaten so severely he never fully recovered mentally.

Watson also remembers being told that his great-grandmother – like many of the captive women – was clever enough to sew money into her dresses to stop it from being confiscated by her captors, and this gave the family some income after the war.

One of the most confronting things Watson said he learned was that women in Lampersari were often coerced into having sex with Japanese soldiers in order to get food, and he believes his film is the first to reveal this in a documentary.

At the end of the war, the Australian Red Cross rescued many of the internees on a hospital ship, as at the time the Indonesians led by Sukarno were throwing a bersiap (revolution) to gain independence and were brutally attacking and killing Dutch civilians. Holman family members were among the lucky ones, taken by ship to Australia for a six-month stay in a Sorrento seaside hotel to recuperate.

While the story is one of hardship and terror, Watson says his grandmother’s time in Sorrento changed her life and set the course for a happy future.

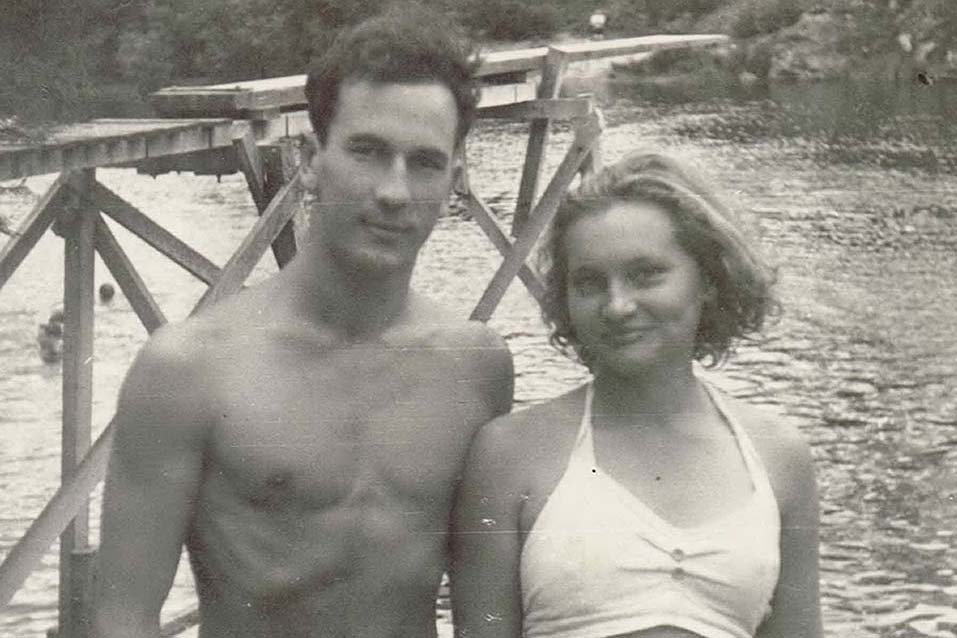

She met RAAF pilot Thomas Watson, who followed her to Amsterdam when she left the camp and asked her to marry him.

The couple later moved to the UK, and then back to Australia, eventually having five children (one passed away at birth) and making a new life together.

Watson, 30, says making the film, which is available on Vimeo and has been shown in Sydney and The Hague, was a “cathartic” experience, as he now feels he understands his grandmother a bit more.

“It was a brief period of her life, but I felt it needed to be told,” he said. “And I have discovered that telling her story has enabled me to get close to her in a way and have that intimate connection with her that I wanted.”

The Past Ended on Mango Street can be viewed at vimeo.com/ondemand/tpeoms

First published in the Southern Peninsula News – 15 February 2022